Understanding the Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act

- By:

- Bill Tolson |

- July 16, 2020 |

- minute read

The evolution of cloud computing has been a boon to companies needing to store and manage their ever-growing volumes of digital data cost-effectively and securely. However, by relinquishing direct control of their corporate data to a third-party cloud provider, companies have made it easier for governments and others to obtain their data without them ever knowing.

Many believe that the Patriot Act and the subsequent USA Freedom Act provided legal basis for the federal government to access cloud-based data. In fact, the Patriot Act did not create the underlying authorities for the US government to access cloud-based data stored in the US. Those authorities already existed in various criminal statutes and procedures such as the Stored Communications Act and remain subject to the protections of the US Judicial System.

Why encryption in a 3rd-party cloud is not sufficient protection

Many cloud providers will encrypt customer data once it’s in their cloud to provide basic security from outside intrusions. In most cases, cloud providers use their own encryption tools, and generate and own the encryption keys. While this basic practice may guard against today’s pervasive data breaches, it fails to guard against another types of intrusion in the form of government “sneak and peek” warrants. In this case, a government agency obtains a secret warrant directing the cloud provider to provide unlimited access for government search and downloading of client data stored in the service provider’s cloud infrastructure – without letting the client company know.

In some instances, cloud providers will fight a government warrant in court or fight to allow the client to at least know that their data is being accessed. In fact, Microsoft has publicly stated:

|

“There are times, however, when the government comes to us for data and prevents us from telling our enterprise customers that it is seeking their data. We agree that there are some limited circumstances in which law enforcement must be able to operate in secret to prevent crime and terrorism and keep people safe. And while we agree that secrecy orders that prevent us from notifying our customers may be appropriate in those limited circumstances, we also believe there are times when those orders go too far. In those cases, we will litigate to protect our customers’ rights." |

In reality, many cloud providers, especially third-party cloud providers, do not have an issue fully responding to a secrecy warrant, mainly because they don’t have the time or money to actually fight a government warrant issued by the US Attorney General’s Office. This should not be a surprise to potential clients who should always ask about a cloud provider’s stance on government subpoenas – do they fight it or comply with it. Further into this blog, I will describe how your company can defend against this practice of governmental “sneak & peak” orders.

The “Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act”

Fast forward to 2020 and the introduction by the U.S. Senate of a bill that would make it illegal for cloud and device makers to deny data access to client data by government agencies (federal, state, and local?).

On June 23, 2020, several U.S. Senators introduced the “Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act” (LAEDA), a bill designed to strengthen national security interests and protect communities across the country by ending the use of “warrant-proof” encrypted technology (i.e., Apple, WhatsApp, others) by terrorists and other criminals to conceal criminal behavior.

The bill would require service providers and device manufacturers to assist law enforcement when access to encrypted devices or data services is necessary – but only after a court issues a warrant based on probable cause that a crime has occurred. The bill would effectively require technology companies to weaken access or provide a back door to their secure devices/systems to ensure law enforcement can track terrorists and other criminals.

The main provisions of the bill include the following:

Enables law enforcement to obtain lawful access to encrypted data.- Once a warrant is obtained, the bill would require device manufacturers and service providers to assist law enforcement with accessing encrypted data if assistance would aid in the execution of the warrant.

- In addition, it allows the Attorney General to issue directives to service providers and device manufacturers to report on their ability to comply with court orders, including timelines for implementation.

- Any provider issued a directive could appeal in federal court to change or set aside the directive.

- The government would be responsible for compensating the recipient of a directive for reasonable costs incurred in complying with the directive.

The ability of a government agency to invoke a secrecy order is not addressed in the LAEDA bill, but it is an already accepted capability in the U.S. Legal System. Two of the most commonly used gag authorities are National Security Letters and nondisclosure orders issued under the Stored Communications Act, 18 U.S.C. § 2705. There are ongoing legal arguments that Section 2705 nondisclosure orders are unconstitutional, all or nearly all the time.

Preceding the filing of a lawsuit against the U.S. government in April 2016, Microsoft documented 2,576 cases in which the government obtained a court order prohibiting the company from telling the customer their data had been searched. In 68 percent of the cases, the gag order had no expiration date. This meant that Microsoft was effectively prohibited from telling their customers the government has obtained their data indefinitely.

In fact, Microsoft sued to have Section 2705 declared unconstitutional, while Adobe succeeded in convincing a court to strike down an indefinite Section 2705 gag order.

This far-reaching privacy incursion bill, if passed, has the potential of being misused. It invokes bad memories of the FISA (Foreign intelligence Surveillance Act) courts in recent years in terms of the possible impact on individual and corporate data privacy if not managed correctly.

Another concern raised by this bill: if a device or service provider is forced to build in a “back door” to your cloud repository, then cyber-criminals will quickly find it as well, putting you at greater risk of CCPA and GDPR privacy violations., i.e., 2-stage ransomware.

Anywhere but there

Many multi-national companies have voiced concern about the U.S. government pressuring US-based technology and service providers to access and turn over corporate data from both electronic devices as well as cloud repositories based on secrecy warrants.

Even before the introduction of this bill, many companies had requirements that data stored in the cloud be stored outside of the U.S. to guard against secrecy subpoenas to turn over data from specific companies/individuals - and not tell them about the data request or data transfer.

However, this strategy ignores the fact that other countries also have laws in place to enable access to end-user data as well with even less privacy protection against a government. In 2018 the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act was passed and signed into law. The law states if you’re a U.S. resident, your data can be accessed if you place it outside the U.S. in a country “with which the U.S. has an executive agreement”. The law also gives foreign governments (with agreements with the U.S.) the right to request information on their own citizens from U.S. tech companies.

Is there a defense against (legal) government access to your cloud data?

Regardless of what happens to the current LAEDA bill, companies are increasingly concerned about safeguarding the privacy of their corporate data. There are two possible defense strategies to stop government agencies from accessing your corporate data in a cloud repository without your knowledge:

- Keep all data on-premises so that agencies cannot access your corporate data without coming to you first

- Encrypt your data before storage in a third-party cloud and own the encryption keys, again forcing the agency to come to you for access

Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of both options.

Option 1: Don’t move to the cloud, keep your data on-premises

Delaying or stopping your move to the cloud because of concerns for loss of control of your sensitive data may sound like the only option to retain complete control… and until recently was a realistic concern for companies. This strategy would put a halt to your plans for digital transformation and have long-term consequences in terms of costs, personnel requirements, data sovereignty, data security, and cyber-liability.

Option 2: On-premises encryption before movement to the cloud

In the past, companies could not encrypt data (and keep the keys locally) before movement to the cloud due to the simple fact that once encrypted and moved to a cloud, the data was rendered useless for cloud-based management or analysis. Now, with the addition of fully homomorphic encryption (see definition below), data encrypted on-premises can be stored in the cloud and remain fully manageable. Companies can benefit from cloud-based archiving and information management without concerns for unauthorized 3rd-party, or governmental sneak & peek access. The result is the warrant would need to be presented to the company which owns the data (versus the cloud provider), who could decide whether to fight it or not.

This encryption technique is truly the only way to fully secure and manage your company’s sensitive data when stored in the cloud while allowing the full use of the encrypted data in the cloud for ongoing data management, eDiscovery/litigation hold, and analytics.

|

Homomorphic encryption differs from typical encryption methods in that it allows computational processes to be performed directly on the encrypted data without requiring access to the encryption key. This means that the encryption keys can remain securely on-premises while allowing full cloud-based data management and analysis. |

The Archive2Azure archive and Security Gateway

Unlike SaaS-based cloud solutions where the SaaS providers use their own encryption keys to encrypt your data, and sometimes use the same encryption keys to encrypt other client’s data, the Archive360 security Gateway enables encryption of your data on-premises before it's moved into your Azure cloud tenancy – utilizing your company’s own encryption keys – which stay secure onsite at all times. Additionally, your encryption keys can never be accessed or used by Archive360 – or any other 3rd party entity.

This on-premises encryption process has the added benefit of significantly reducing the risk of a data breach triggering privacy regulatory notification requirements – a very costly process. In fact, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) stipulates that the notification requirement is not triggered if the breached data was encrypted AND the encryption keys were kept separately. Even though it is not explicitly stated, it is believed the GDPR authorities would rule the same way if presented with the same situation.

Archive2Azure with the Security Gateway provides the best of information management and archiving in the cloud without the security risks of SaaS solutions.

Summary

Whether this new senate bill, the “Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act,” passes or is replaced by another, the trend in the U.S. is to make it easier for government authorities to access your corporate data – sometimes secretly.

Rather than abandoning or delaying plans to embrace cloud computing, companies need to reconsider their cyber security strategy in order to guard against the misuse of their cloud data. By encrypting your data onsite (and keeping the encryption keys local) before storage in a 3rd-party cloud, you control who accesses your sensitive corporate data, not some SaaS cloud provider. With this data security capability, you will force government agencies to come directly to you to get access to your data.

PaaS versus SaaS: What you need to know

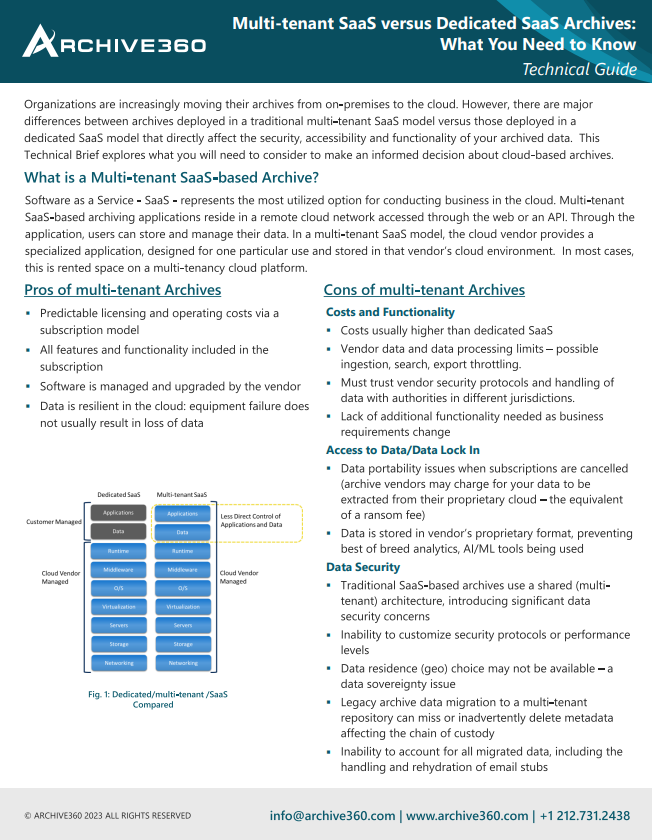

There are major differences between archives deployed in a SaaS model versus those deployed in a PaaS model that directly affect the security, accessibility and functionality of your archived data. This Technical Brief explores what you need to consider.

Bill is the Vice President of Global Compliance for Archive360. Bill brings more than 29 years of experience with multinational corporations and technology start-ups, including 19-plus years in the archiving, information governance, and eDiscovery markets. Bill is a frequent speaker at legal and information governance industry events and has authored numerous eBooks, articles and blogs.